THEY DON'T CALL her a lady painter any more. And though her work is saturated with feeling for the Southwest, nobody calls her a regional painter, either. She's an artist. Just that.

Her fame is international. Yet she's probably one of New Mexico's least-known residents. Georgia O'Keeffe prefers it that way. They've labeled her an abstractionist, a realist, an impressionist, a surrealist, a pop artist, a hard-edge painter—a recluse. Georgia O'Keeffe, who is all of these things and none of these things, continues calmly to lead her own life, to paint what she sees and feels, to carry on her love affair with the land that is New Mexico. The unreliable winds of public favor have never changed her view of herself or her work.

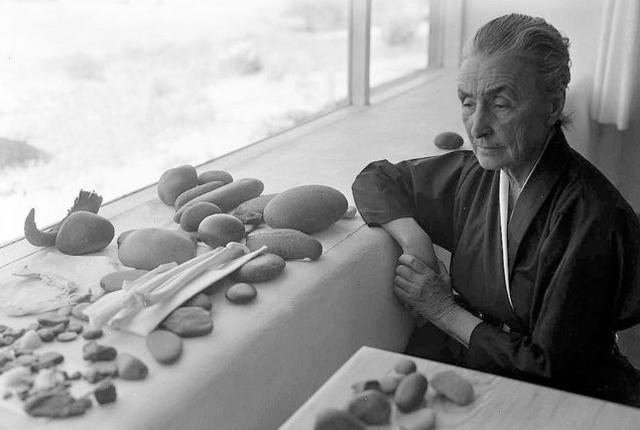

She's 85, but, clad in jeans, jacket and white shirt, clear of mind and purpose, she might be a youthful and agile 60.

It was in 1917 that Georgia O'Keeffe first saw New Mexico—on a three-day detour through Santa Fe with a younger sister. "From then on I was always on my way back," she says now with that fleeting, knowing smile. O'Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wis., and her early years were spent there and in Virginia. It's reported that at 10 she had decided to become an artist.

Art training was rigorous and formalized in those days. The idea was to paint exactly like the European masters. An apt student, O'Keeffe won prizes. But then as now she had that clarity of vision—and what she saw was that all her work was derivative, reflecting this or that teacher's style and viewpoint. And she was not one to be satisfied with being a copyist. O'Keeffe was a strong-minded as well as beautiful young woman. She gave up painting.

Fortunately, a couple of years later, a sister persuaded O'Keeffe to try a new teacher at the University of Virginia—Alan Bement, a disciple of Arthur Dow, who patterned his teaching on the design principles of Japanese and Chinese art.

"It was Arthur Dow's ideas that made me find something worthwhile to work on," O'Keeffe says.

She eased back into painting, and found a job teaching in the public schools—but not in the comfortable cultural milieu of the East. Amarillo, on the desolate plains of west Texas, was like the ends of the Earth to most Easterners in those days. To O'Keeffe, Amarillo was an awakening, her first experience with the "wonderful emptiness" of the Southwest, and the beginning of her attempts to paint her own way. "Sometimes when the plane flies over Texas, and I see those plains below, I think I want to get off right there—and stay!" she says.

One day, she sent a few of her new drawings to a former classmate in New York, with the caution to show them to no one. The friend was so excited she took them to Alfred Stieglitz, the great photographer, gallery owner and discoverer of modern artists. The rest is history. Stieglitz was enraptured and hung the drawings in his gallery. O'Keeffe heard about it when she was back in New York, and stormed the place to demand that they be taken down. The drawings stayed up. And in 1924, Stieglitz and O'Keeffe were married. But in many ways, she remained a loner, true only to her own star. She never became "Mrs. Stieglitz" —she remained "O'Keeffe."

In 1929, she came back to Santa Fe. Just for a visit. "The first day, I went to an Indian dance at San Felipe," she says in recollection. "And there I saw Tony Luhan—I' d met him and Mabel Dodge Luhan previously in New York. Tony came over to speak, and then Mabel said, 'You must go to Taos with us.' I told her I didn't have time and, though she persisted, I thought that was the end of it.

"In the morning, there was Mabel at the hotel door. She'd already sent my trunk up to Taos—we traveled with trunks in those days. So, we went along." She pauses and laughs. "Tony rented me a very fine studio, and I had the house the Lawrences (D. H. and Frieda) had the year before. There was a large alfalfa field with a black horse and a white horse, grazing in front of the mountains. It was a great summer ... " There are other memories of the early days in New Mexico.

"I got a car in Taos, and Tony was going to teach me to drive. We started out, toward the morada (chapel) in back. And there was a fence, and the gate was closed. I threw up my hands and said 'What do I do now?' because he hadn't taught me how to brake! That was my last lesson with him." She learned to drive, however, thanks to Charles Collier of Los Luceros, son of John Collier, the famous director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and she traveled around the area extensively, drinking in the essence of the stark, uncluttered landscape.

"Charles told me there was a place I hadn't seen yet, a place he thought I'd like ... and he drove me out past Ghost Ranch." Driving around northern New Mexico in those days wasn't the simple job it is now. Settlements were few, the miles long, the roads dirt.'' And only a single track, at that," O'Keeffe adds. Ghost Ranch was a remote, wildly beautiful acreage, northwest of the tiny Spanish-American village of Abiquiu. ''We drove up and down, but we couldn't find the gate to the ranch, and we had to go back." By then, tired of the Taos social whirl, she was renting a place in Alcalde, north of Española.

Read more: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Radical Abstraction marries the conceptual to the real.

But Ghost Ranch seemed to be in her destiny. During the next winter in New York, she met people who knew a man who was building a house on Ghost Ranch and who claimed it was "the best place in the world." Then, the following summer, 1934, while she was shopping at the San Juan Mercantile ("It was like a trading post out on the Navajo reservation in those days. You got your high button shoes there!"), O'Keeffe spotted a car with "GR " on it. "I waited for the man to come out, and he told me how to find Ghost Ranch. He said there should be a horse's head on the gate. So I drove out the next day to look for it.

"Ghost Ranch was a dude ranch, I was told—and I thought dude ranchers were a lower form of life," she says, and the amused twinkle flashes in her eyes. "But anyway, I asked if I could spend a night there sometime. I wasn't sure I could live with dude ranchers."

She got the chance the next day when a room was available for just one night. ''And that night, a family came, with a boy who developed appendicitis. They had to leave and I got their rooms. I went immediately to Ghost Ranch to stay. And I never left."

But that was only in the summers. The rest of the year she spent in New York and at Lake George with her husband. To most people, except those in the art world, she was primarily Stieglitz's wife and famous model. And, oh yes, she also painted. Quite well ... for a woman ... if you liked that sort of thing … Her summers in New Mexico began as two-month trips. "But I kept stretching the summers to four and five months," she says, smiling mischievously. "I knew I'd eventually live here."

Stieglitz never came to New Mexico himself. "What, and be 50 miles from a doctor?" O'Keeffe laughs out loud at the thought of her urbane, city-oriented husband in the remote badlands of New Mexico in those distant days. Meanwhile, she tried to paint what she felt about the mountains, the mesas, the desert. "I liked the idea of putting it down, but I felt I'd completely failed," she says. Others didn't think she'd failed. Her "failures" are now in museum collections. Typical—if any of her paintings is typical—is a looming, close view of a black cross and the distant sunset-lit hills. The stark, brooding cross somehow tells all there is to know about life in a small Spanish-American Catholic village in northern New Mexico.

Each year, when O'Keeffe went back into her husband's orbit, she took mementos of the West. Stones, weathered and worn smooth. Artificial flowers. ("They were popular then, and there were some very lovely ones being sold in the country stores here.") And desert-bleached bones. "To me they are as beautiful as anything I know," she once wrote. "To me they are strangely more living than the animals walking around—hair, eyes and all, with their tails twitching. The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even tho' it is vast and empty and untouchable—and knows no kindness with all its beauty."

"I took back a barrel of bones," she says now, her eyes amused at the recollection. "I remember it cost me 16 dollars by freight." One wonders at her husband's reaction to this delivery. Whenever she began painting something new and different, she says, Stieglitz became worried, wondering what she was doing. But, inevitably, when the work was finished, she says in amusement, "he gave in," and appreciated her new direction. It was that way when she began painting the bones. And the artificial flowers in juxtaposition with the bones. Her painting of a bleached cow skull with a pink rose in its eye socket caused a sensation when it was reproduced in color in a national magazine in 1938.

She recalls one of her first brushes with her new-found fame. "I had a car that year in New York. When I went to the garage to pick it up and gave the mechanic my name, he said, 'Why, I know you. I have a picture you painted on my living room wall.' He'd cut it from the magazine. Imagine that!" Her voice is still amazed at the memory.

The paintings also brought out the amateur psychologists among the critics, who immediately found symbolism of life, of death, of eternity and, of course, of sex. "They've made up odd tales about the skulls and flowers," O'Keeffe says. "But it was just a little thing. I had the flowers and I had the bones, and I put them together. It didn't happen any other way."

Some critics have also called her paintings "stylized," "hard"—and, in recent years, "hard-edge." The last is an easy, pop term. Perhaps better too easy. "Precise" might be a better word. There is little that is hardlooking in O’Keeffe’s paintings. The superbly delicate tone shading gives objects a sensuously molded look. Critics managed to find sexual connotations as well in her supersized flower paintings, paintings she has sometimes made in series analyzing a given flower, and getting closer and closer to its truth.

Strangely, many motifs recur in her paintings over the years. A doorway of a studio in New York in 1919 is echoed in the painting of a doorway in her Abiquiú patio in 1946. Crows over Lake George in 1921 appear again when a blackbird flies over red hills of New Mexico in 1946. A 1925 tree in Lake George has the same feeling as cottonwoods painted in 1954. And in recent years, those breathtaking early abstractions again appear in new and larger forms. It’s as if her work had progressed not in a circle, but in an upward spiral.

New Mexicans can watch for another recognizable motif that recurs in painting after painting—a mesa-topped mountain, familiar to anyone who lives in northern New Mexico as Pedernal. O’Keeffe calls it merely “My Mountain.” As the years passed, O’Keeffe bought the house she’d rented at Ghost Ranch. Later, after years of negotiating, she also bought a house in Abiquiú, one she could use in winters as well. “And where I could have a garden,” she adds. “I do a lot of work outside,” she says, “and I needed a place to stay, a place to eat. There was no restaurant in Abiquiú then, and there’s none now.” The house, and old adobe ruin— “pigsty!”—on a bluff above the startling green of the Chama River valley, had to be completely restored before she could move in.

Read more: Ghost Ranch's tour manager answers even the questions visitors don't know to ask.

Here’s something nobody has written,” she adds. “When we were reading the old deeds not long ago, we found the place had been sold back in 1826 for two cows, one with calf, a bushel of corn—and a serape!” She laughs, delighted with the information. After Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe became a permanent resident of Abiquiú. She became a part of the small community, yet apart from it. The remote spot protected her need for isolation, and gave her the time and the place she needed for painting. There, as at Ghost Ranch, she lives the life that is, like her paintings and herself, deceptively simple, elegantly austere. And now, after more than half a century of painting her “own way,” her popularity continues to increase. She expresses surprise at that, calling herself and “old-fashioned painter.”

She seems astonished at the mail that continues to pile up. “There’s a stack two-feet high” of opened letters on her desk from young people who have seen a show or read an article “in some old magazine in a dentist’s office” and identify with this remarkable woman. Many want to meet her, to talk to her. And still the letters pour in, from old and young. “I’d like to answer the lot, but there are so many,” she says. The rest is left unsaid. Her time, her solitude are her most valued possessions—the very things that have allowed her to be herself.

“They tell me my shows outdraw everyone except (Andrew) Wyeth,” she says, pleased, bemused. But you get the feeling that deep down, it doesn’t matter. She’d have painted the same way, lived the same way, no matter what the rest of the world thought. “I’m very lucky to have found my time—not everyone does,” she says.

And her place. New Mexico. “It was a new world,” she says of her first ecstatic views of New Mexico.

“And I thought this was my world.”