A SHORT TIME AGO, I went out to San Ildefonso Pueblo Santa Fe, to see María Martinez, the great potter and my friend of long standing. I took with me a large photogravure of a picture taken by Edward S. Curtis, the famous photographer, in 1905. Its subject was a corn dance there.

I was making a gift of the Curtis print to the pueblo. Before presenting it to the governor, I wanted to see how many people María could identify of perhaps 40 shown. To my surprise, she named at least eight among the dancers and chorus from that long ago.

Several friends joined us. There were “oohs!” at the sight of the small cottonwood that today is a great tree in the pueblo’s north plaza. María and I sat under the portal of her son’s house. It was a lovely summer day, no wind ... only the rush of children running toward the tree in a field day event on this Santiago Day.

We dropped in to reminiscence about persons known to both of us. María spoke first of the late Dr. Kenneth M. Chapman, the eminent anthropologist. As far back as 1908, she said, Dr. Chapman “was the one to encourage Julian and me in our early pottery-making.” María was shaping the pots and her husband decorating them with sure, skillful designs. This was the beginning of their lifelong achievement.

María spoke of Dr. Chapman’s interest in the variety of design, the perfection of her pots, bowls, and plates. (He expressed this admiration in his book The Pottery of San Ildefonso Pueblo.)

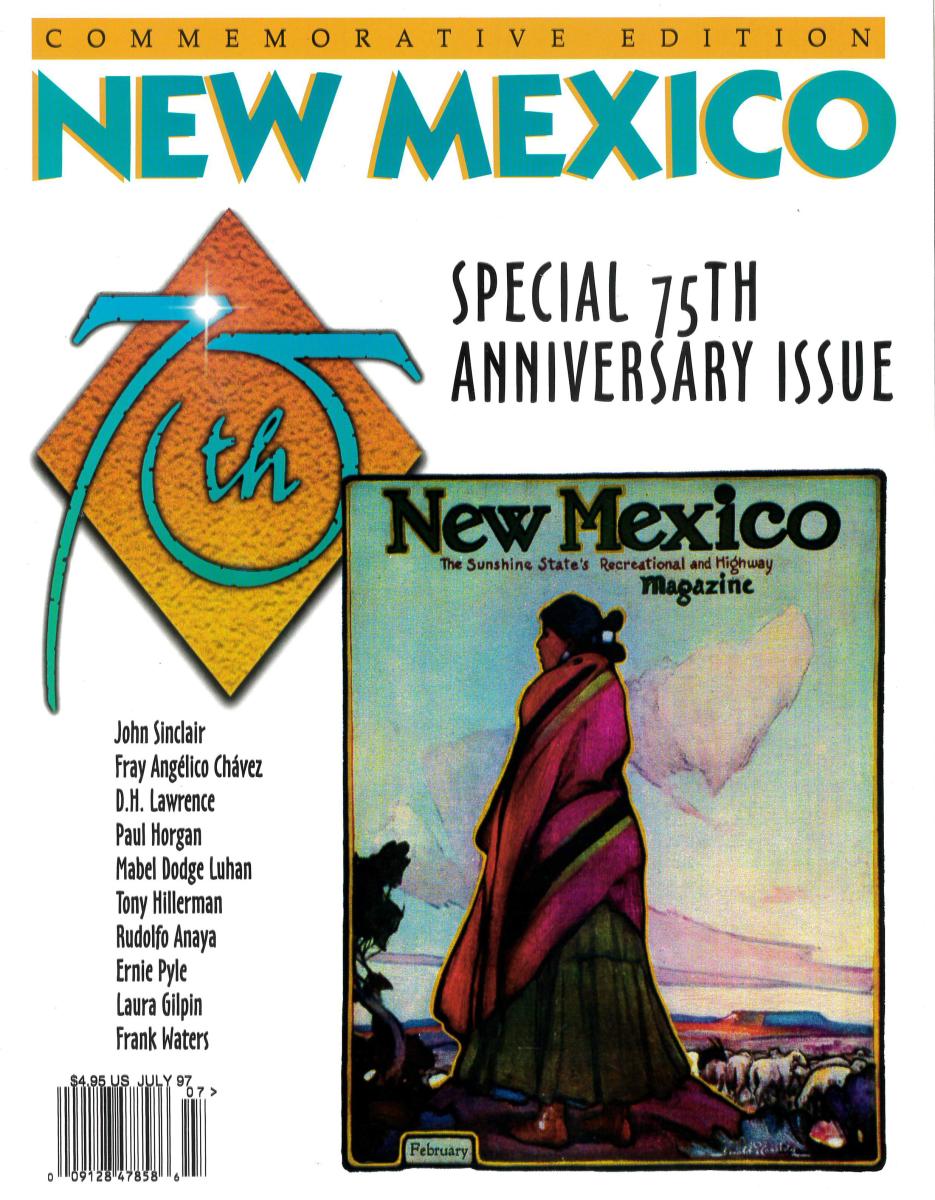

ON THE COVER

Art director John Vaughn and assistant art director Daniel Martinez incorporated a February 1933 cover, which features The Navajo Shepherdess by Gerald Cassidy, into the design for our 75th anniversary.

María recalled the late Dr. Edgar L. Hewett, first director of the School of American Research, who superintended early excavation at what is now Bandelier National Monument, west of San Ildefonso. She visited there when Julian worked with the archaeologists. She also visited them at nearby ruins of Tsankawi, Otowi, and Puye.

“Dr. Hewett became not only a good friend of ours,” María said. “He was a firm friend of all our Indian people.” Similarly, she said, were such other noted anthropologists as Dr. Alfred V. Kidder, Jess Nusbaum, and Dr. Sylvanus Morley, all now dead.

María mentioned Ina Cassidy, wife of Santa Fe’s famed painter Gerald and an art critic in her own right. ... Edith Warner, who operated a celebrated teahouse near Otowi Bridge where scientists congregated during the war-time years of secret nuclear development at Los Alamos. ... Mary Van Stone, who helped many Indians sell pottery during years of association with the Santa Fe Art Museum. It was through the museum, incidentally, that María and Julian first sold their now coveted black-on-black pottery.

QUOTABLE

“[Photographer Harvey Caplin] was as much at home on a horse as he was with his camera. Indeed, his many ‘working cowboy’ photographs were taken from atop a horse while he lived the daily life of the cowboy—gathering cattle, cutting, branding, busting broncs, and even just eating and sleeping. These photographs reflect the tremendous energy and rugged work that was the cowboy lifestyle, yet they capture the vivid majesty of the cowboy and his horse—his working partner—in mastering the job at hand.”

—from “Focus on Harvey Caplin,” by Debbie Tissot

María told me laughingly of a youngster who asked: “Grandma, how could you get those degrees when you never went to college?” The grandchild was referring to honors conferred by the University of Colorado and New Mexico State University.

She threw up her hands. “How could I answer?”

The answer is that María’s education came with the beauty she brought to her art ... an education at which she stands at the highest level as attested by many medals, citations, and trips all over the country to demonstrate her skills.

Despite the bustle of modern life, San Ildefonso still lies quietly beside the Río Grande, its people resting on a dignity born of generations and an acceptance of life as it comes. As María had accepted Julian’s passing in 1943. She is about 86, and when I took my leave, I was refreshed from her presence and newly aware of the deep richness of her life. She is a beautiful person.

Read more: All aboard for a trip back to the heyday of narrow-gauge railroads.

Editor’s note: Born in 1891, Laura Gilpin photographed the Southwest and its people for more than 60 years. She originally wrote this profile on potter María Martinez for the January 1974 issue of New Mexico Magazine. It was reprinted in the July 1997 issue.

O’KEEFFE’S WORLD

They don’t call her a lady painter anymore.

And though her work is saturated with feeling for the Southwest, nobody calls her a regional painter, either.

She’s an artist. Just that.

Her fame is international. Yet she’s probably one of New Mexico’s least-known residents. Georgia O’Keeffe prefers it that way.

They’ve labeled her an abstractionist, a realist, an impressionist, a surrealist, a pop artist, a hard-edge painter—a recluse.

Georgia O’Keeffe, who is all of these things and none of these things, continues calmly to lead her own life, to paint what she sees and feels, to carry on her love affair with the land that is New Mexico. The unreliable winds of public favor have never changed her view of herself or her work.

She’s 85, but clad in jeans, jacket, and white shirt, clear of mind and purpose, she might be a youthful and agile 60.

It was in 1917 that Georgia O’Keeffe first saw New Mexico on a three-day detour through Santa Fe with a younger sister. “From then on I was always on my way back,” she says now with that fleeting, knowing smile.

Editor’s note: This story, originally titled “My time …. my world,” first appeared in the January 1973 issue of the magazine and was reprinted in May 1986 following artist Georgia O’Keeffe’s death. It was reprinted again in the July 1997 issue to coincide with the opening of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, in Santa Fe.