Acoma Pueblo is an excellent example of classic Puebloan architecture. Photograph by Gabriella Marks.

In Mud We Trust

Back to Top of ListFIRST CAME THE HAND-FORMED MUD structures of the Puebloans. Then the adobe bricks of Spanish colonists arrived. The railroads brought milled lumber and kiln-fired bricks. Today, “faux-dobe” buildings (stuccoed wood-frame construction) crop up throughout New Mexico—the so-called Santa Fe style that embodies our architectural spirit.

Numerous architects planted the modern-day seeds, but John Gaw Meem wears the crown as the 20th century’s chief historian, preservationist, and visionary.

“Meem really studied the traditions more deeply than anyone,” says Chris Wilson, the regents professor of landscape architecture at the University of New Mexico and author of Facing Southwest: The Life & Houses of John Gaw Meem (W.W. Norton, 2002). “He was trained before modernism, so he believed in historical precedent and typologies and strived to incorporate those into his work.”

A young John Gaw Meem, before he achieved regional fame. ZIM Center for Southwest Research Pict Colls PICT000-675NJS.

In the 1930s, Meem oversaw the WPA’s Historic American Buildings Survey in the Southwest, directing architects to draw and measure buildings that featured classic Pueblo, Spanish, and Territorial styles. He dove into preservation of mission churches, including Acoma Pueblo’s San Estevan del Rey, and designed the 1939 Cristo Rey Church, in Santa Fe.

He came to Santa Fe in 1920 as a young man suffering from tuberculosis, and when he died, in 1989, he left a legacy of iconic structures—the Museum of International Folk Art, in Santa Fe; Fuller Lodge, in Los Alamos; and 35 buildings on the UNM campus. “He brought Spanish Pueblo Revival architecture to maturity and then developed Territorial Revival in the 1932–34 period,” Wilson says. “He’s kind of the fountainhead of New Mexico regional design, history, and preservation.”

Hit the Road

Back to Top of List The historic Lincoln County Courthouse includes elements of Territorial-style architecture. Photograph by Efrain Padro/Alamy.

The historic Lincoln County Courthouse includes elements of Territorial-style architecture. Photograph by Efrain Padro/Alamy.

Hit the Road

Acoma and Taos

For classic Puebloan architecture, these living examples of multistory adobe buildings reveal green technology that was centuries ahead of its time. Chris Wilson notes that the builders took advantage of earthen mass and L- or U-shaped designs to control interior temperatures and used a southeast orientation to honor a sacred cosmological direction. “Alfonso Ortiz [an Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo anthro-pologist] talked about how keyhole-shaped kivas in some Pueblo traditions were placed in front of an L-shaped building with a southeast orientation,” Wilson says.

San José de Gracia Church

One of the finest examples of Spanish Colonial architecture in the state, this mission church in Las Trampas, on the High Road to Taos, was founded in 1751 and holds rare examples of santero artworks inside. “It was open more often than not in past summers,” Wilson says. “If you’re driving the High Road, stop and see if it’s open and, if so, that’s a real treat. Leave a donation as your thanks.”

Lincoln

Most of the town that Billy the Kid made famous is today a state historic site that reveals the elements of Territorial-style architecture, including a rare two-story adobe courthouse that was built as the Murphy-Dolan Store. “All these buildings haven’t changed at all,” says Tim Roberts, deputy director of New Mexico Historic Sites and co-owner of a craft brewery in Lincoln. “This is where east meets west—traditional Southwestern styles with East Coast influences.”

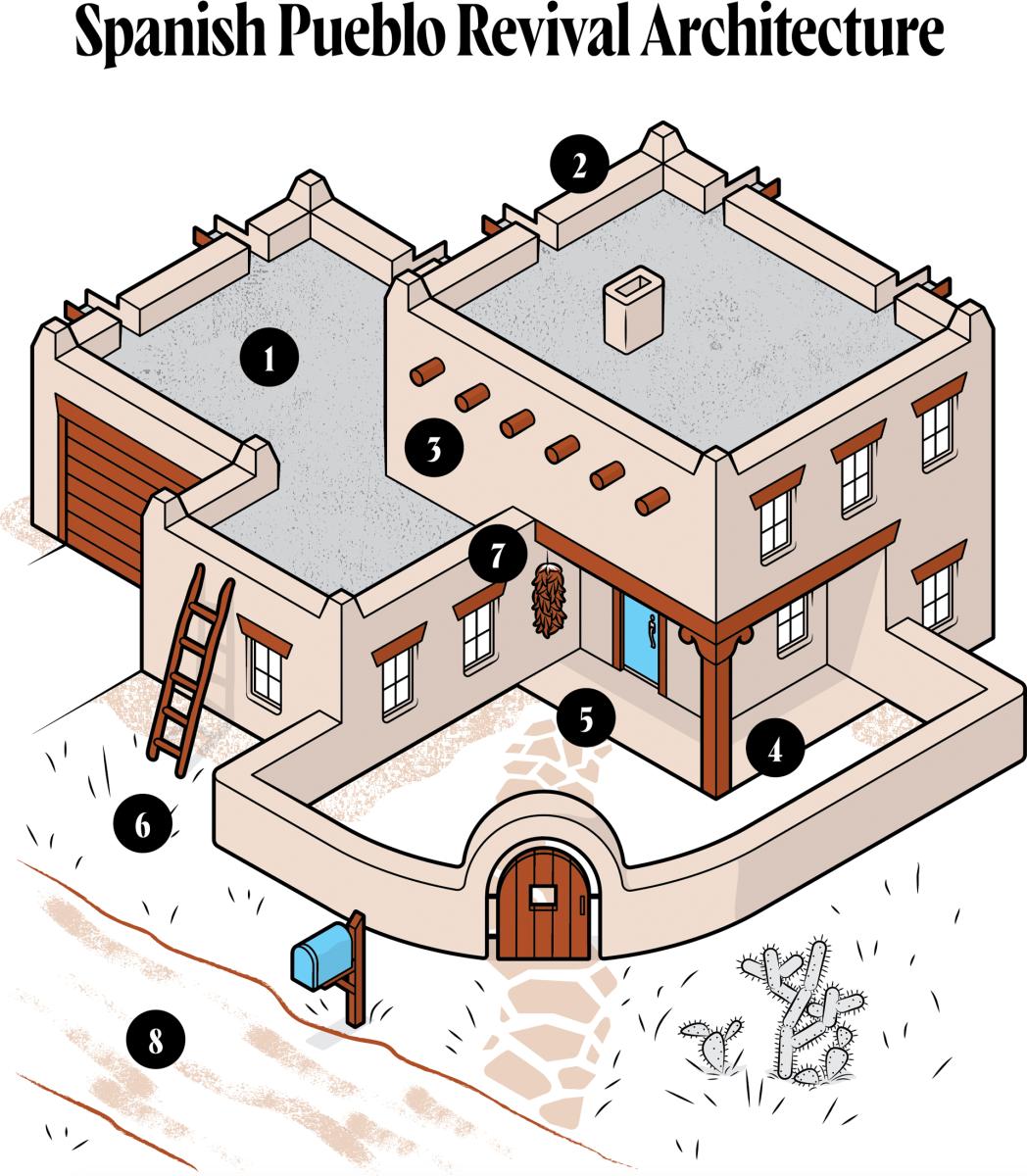

Spanish Pueblo Revival Architecture

Back to Top of List There are many elements that make Spanish Pueblo Revival Architecture unique. Illustration by Chris Philpot.

There are many elements that make Spanish Pueblo Revival Architecture unique. Illustration by Chris Philpot.

Spanish Pueblo Revival Architecture

-

Flat roofs have a slight tilt so water runs off via canales (or so you hope).

-

Parapets add architectural interest to the roofline.

-

Vigas, pine logs that support ceilings, often jut out of the roofline.

-

An inset portal, or porch, creates a shady spot.

-

Painting your door blue is rooted in a belief that it scares off bad spirits.

-

A ladder made of aspen or pine poles called latillas makes it easier to fix the inevitable leaks in that flat roof.

-

Hanging a ristra of red chiles cheers up the entryway.

-

A dirt road often drops a clue: expensive real estate ahead.

The Best: Kivas

Back to Top of List The kiva at Pecos National Historical Park is open for visitors. Photograph by NMTD.

The kiva at Pecos National Historical Park is open for visitors. Photograph by NMTD.

The Best: Kivas

For centuries, Puebloans have carried out their most sacred ceremonies inside kivas, round or square earthen structures that act as the heart chamber of the tribe. Active kivas are off-limits, but you can climb down into a historic one at Pecos National Historical Park and step into the grand kiva at Aztec Ruins National Monument, where Chaco-era cultures once gathered. The interior walls of the kiva at Coronado Historic Site, in Bernalillo, are covered with mud paintings that serve as visual prayers. The original murals—17 layers thick—were removed and preserved during the Depression. In 1938, Zia Pueblo artist Ma Pe Wi (Velino Shije Herrera) re-created them, an homage to the Kuaua Pueblo people who once lived there.

The Worst: Howling Coyote Statues

Back to Top of ListYou've probably seen one or two of these back in the 1980s. Illustration by Chris Philpot.

The Worst

Howling coyote statues by the front door became so popular in the 1980s and ’90s that their persistence draws eye rolls today. Pile on the clichés by painting yours turquoise and tying a red bandanna around its neck.