Patrice Mutchnick inspects a leaf of dock (Rumex sp.), a common riparian plant in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument.

AS WILLIAM NORRIS AND RUSS KLEINMAN drive through the pink rhyolite-lined canyons along the Gila River on an April morning, Norris mentions one of the notable gaps on a list of plant species found over the past decade at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. A plant survey years ago found several species of Descurainia, a family of tansy

mustard, but in his group’s nine years of fieldwork here, they’ve found only one.

“So if you see one that’s not that one … ” Norris says to Kleinman, the expert on this type of plant and the person among them most likely to spot one of the Descurainia species they haven’t yet documented.

In 2013, Norris, who teaches botany at Western New Mexico University, in Silver City, and a team of scientists, including Kleinman, began inventorying all the plants growing at the national monument. Eight years later, on that April morning, they’d counted 512 species. That’s roughly 10 percent of all plants known to live in the state of New Mexico, found in a study area of less than one square mile. The varied topography squeezed into such a small footprint—sunbaked grasslands on the mesas, rocky cliff bands, the humid

corridor of the creek through Cliff Dweller Canyon, and the meadows, riverbanks, and backwaters of the Gila River’s West Fork—aids the abundance.

Patrice Mutchnick stands by swamp sedge (Carex senta). Biology professor William Norris.

Patrice Mutchnick stands by swamp sedge (Carex senta). Biology professor William Norris.

Part of the point in making this kind of record is to know what’s here now—to document the astonishing biodiversity as a bit of a time capsule, particularly with the quickening pace of climate change.

“If I were reading about places and someone showed me this list of 500 species, I’d go, ‘Wow, that’s a rich site. I want to go see that,’ ” says Kelly Kindscher, an ethnobotanist who travels from Kansas to southern New Mexico to work on the project each summer. “The Gila is just a wonderful place, so it’s exciting to get down there, learn the flora, and help make new insights. The Gila truly is of national significance.”

The range of expertise on the team has helped build a robust list of species. Norris is good at (the notoriously tricky) grasses and sedges. Kleinman’s dialed in mosses and ferns. Kindscher knows prairie plants and, as an ethnobotanist, plants used by ancient peoples. Richard Stephen Felger led the way in a book on the region’s trees. And Patrice Mutchnick champions native species, helping them thrive through the nonprofit she founded, Heart of the Gila.

The work is open-ended scientific inquiry: a catalog of what they find.

“A lot of folks call this ‘old-time botany,’ ” Norris says. “But guess what—old-time botany has a lot to teach us.”

The water–crowfoot (Ranunculus aquatilis) and Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii) can be found at Gila Cliff Dwellings.

The water–crowfoot (Ranunculus aquatilis) and Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii) can be found at Gila Cliff Dwellings.

Inventories like this one shine light in two directions. Knowing what’s there now illuminates how the place may have already changed and how well native species have held on through centuries of new arrivals to the area. It’s also a beacon for future researchers to look back on, a baseline for measuring how much the region continues to shift from then to now.

Compiling a thorough look at that baseline requires scouring the canyon end to end, hiking miles in from distant trailheads to reach the canyon rims, browsing thickets along the riverbanks—like a flea market full of surprises—and scrambling over loose, rocky terrain to seek out clandestine springs and shady pockets. The work is physically demanding, mentally tricky, time-consuming, and detail-oriented.

The clearest signal that the survey is winding down comes from how hard it has become to find something they haven’t already documented. Early on, a day’s work could yield 15 to 20 plants—as many specimens as they could successfully document, collect, and preserve. But in 2020, they found about as many new plants all year as they used to find in a day.

Each day when they set out, question marks await. Will they find something new? Will they fill in one of the curious omissions? Or has the canyon shared all that it can?

Russ Kleinman inspects one of the many moss species he has collected.

Russ Kleinman inspects one of the many moss species he has collected.

TO SHOW ME THE PLACE and what goes into the work, Norris, Kleinman, and Mutchnick meet me at the cliff dwellings. We gather near a bridge over the river as cottonwood seeds drift on the morning breeze, then hike at a ponderous pace up the trail. Hikers brush past us heading toward the dwellings while we pause to talk about the greenery, from towering ponderosa pines to the scruffs of moss on trailside rocks. Cliff Dweller Canyon cuts deep into blondish tuff, remnants of an ancient volcano’s crater. Though other canyons slice into that same tuff, only this one hosts a stream that runs all year.

“It’s a little bit of a magic thing,” Mutchnick says of the stream, the mosaic of ecosystems it creates, and the community it once supported. Dandelion leaves poke out of her pockets; she’s nabbed the European invader where it grew within reach of the trail. “The water has to be a reason Native people lived here, and it’s definitely a reason the biodiversity is so high.”

The canyon became a national monument in 1907 to preserve the cliff dwellings, but that status also shielded native plant species. What grows now largely matches what grew at the height of the Mogollon culture, echoes of life from a thousand years ago. The roof beams those people laid in place were cut from junipers, oaks, and pines, the same trees that still lattice into the few shady strips over the trail.

Read More: A hike in the Gila National Forest trains the eye to follow what matters most.

A New Mexico olive’s tiny, bright-green leaves brush our sleeves as we hike by an early violet’s white blossoms and tufts of puccoon,

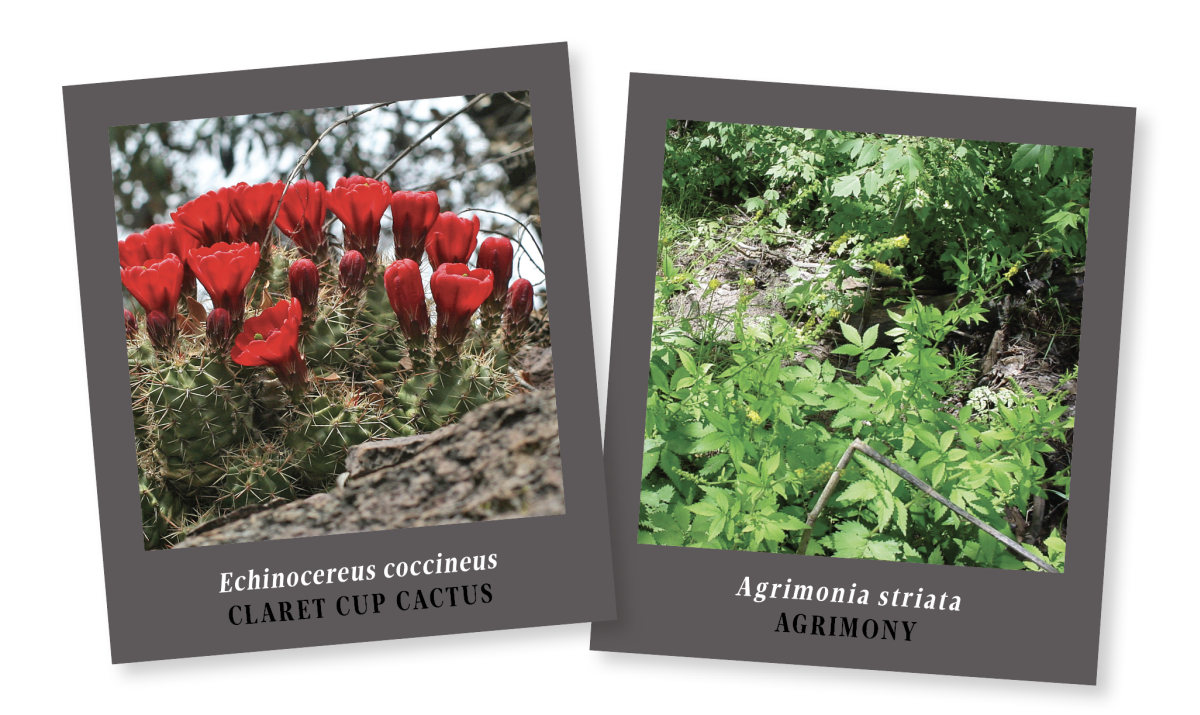

a tallgrass prairie plant Norris knows from fieldwork in Ohio. Tall, with a bushy white beard and a botanist’s classic forward tip to his shoulders, Norris tends to hike ahead, hands in his pockets, pausing to point out something that catches his eye. That means marveling at the view of a claret cup cactus from below as it blossoms on a ledge above the trail, or taking in a swath of false Solomon’s seal, a plant he knows from his youth in Michigan and welcomes like an old friend. But here it grows near surprising company. The slender, emerald leaves of the shade-loving plant share a hillside with banana yucca, a familiar presence in the sunny Southwest.

Where the trail squeezes along a shelf of sandstone and the dwellings loom overhead, Norris and Kleinman stare at a cluster of plants the next ledge down. Kleinman, a retired surgeon who started his education as a botanist by asking Norris to give him a tour of the piñon-juniper scrublands around his house, is looking at what he’s fairly certain is a new Descurainia.

Mutchnick’s eyes lock onto it. She dons a yellow-and-orange National Park Service vest—“our ticket to travel anywhere,” she jokes—then scrambles down a shelf of rock half as tall as she is, stepping carefully to avoid knocking rocks off or crushing other plants.

Collecting a plant sample means trying to get as much of the entire specimen as possible—flowers, stem, leaves, and roots. It’s not enough to pick a couple of leaves. The first step is to check for multiple plants of the same species nearby, to avoid removing the last of something from the wild. Once that is confirmed, Mutchnick’s fingers work some of the dirt away from the wispy plant, its leaves like tiny clenched fists at the ends of tendrils, its stem not much thicker than a toothpick. Then she tugs it loose.

By looking longer, they spot a dark green fern, its leaves thickened in the way plants that know how to grab and hold on to water do. It could be a second new species. They take just a couple fronds of this bushy one, low enough to catch some of the texture at the base.

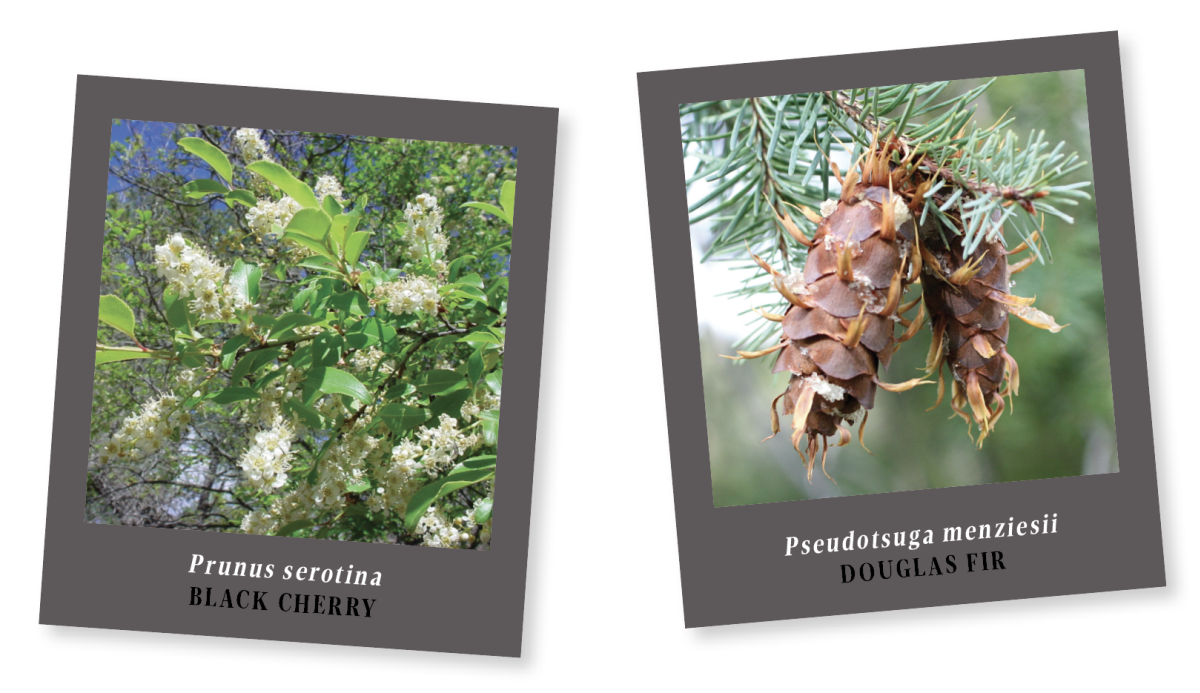

Botanists have identified black cherry (Prunus serotina) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) at Gila Cliff Dwellings.

Botanists have identified black cherry (Prunus serotina) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) at Gila Cliff Dwellings.

Norris pulls a yellow notebook, plastic bag, and GPS unit from his backpack, writes down the geographic coordinates, plus the location, date, time, and names of everyone present. He notes a description of the dry, sunny, south-facing slope overlooking Cliff Dweller Creek, and other plants growing nearby: Engelmann prickly pear, banana yucca, cloak fern, piñon pine, juniper, mountain mahogany. His eyes gleam as he turns to me. “I’ve been really looking forward to this,” he says.

But the celebration is muted by uncertainty. Norris won’t know for sure what he found until he has these plants back in the lab, examines them under a microscope, and cross-checks the list to make sure they are indeed newcomers. Two of the researchers must agree on an identification before it’s settled. (Do disagreements get tense? “Well,” Kindscher tells me later, “we’re friends.”)

Then Norris slips the samples into a plastic bag for the hike back to the plant press in his car. Once at his house, they’ll come out of the bag and be placed on blotter paper, then flattened under books, preferably with the leaves and petals spread for permanent display. If either proves to be a new species, the details of when and where it was found will be typed onto a label that joins the specimen in WNMU’s herbarium, which Norris curates.

They’ve preserved a physical sample for every species on the list. That allows for double-checking in case of a name change, new classification, or recategorization, which is a semi-regular occurrence these days, thanks to DNA analysis.

The finding, if it is one, demonstrates a basic principle of plant surveys, Norris says as we resume hiking. An effective survey requires fieldwork in the same location, at different times of the year, over many years. Plants grow and die off, meaning what’s there in early spring is invisible by summer. Some plants emerge only in particularly wet or warm years.

Norris’s teaching schedule rarely allows for being in the field before the semester ends, but for my benefit he came out a couple of weeks earlier in the spring than usual. That variance may have allowed him to catch an early spring arrival that’ll be gone by the time his grades are filed in mid-May.

They’ve tinkered with these variables before—targeting pockets of habitat, seeking out damp microclimates around some of the seeps and the dry, rocky slopes, and visiting during a range of weather conditions, such as after a wet spell. “It’s kind of a hide-and-go-seek game,” says Kindscher. “It’s finding pieces.”

We turn back toward the visitor center, full sun baking the canyon, passing southwestern chokecherry and wild roses, which are marked by the pinched teardrops of last year’s rosehips and the nubby starts of this year’s thorns.

Of the plants previously recorded at the Gila Cliff Dwellings—species they have every reason to think were here then (and therefore aren’t mistakes, though there may be some of those, too) and might still be here—they’re missing about 80 to 90 plants.

“The one thing about projects like this,” Norris says, “is you never find them all.”

William Norris explains a woody plant species to his dendrology students.

William Norris explains a woody plant species to his dendrology students.

IT'S POSSIBLE THAT THEY HAVE MISSED THEM, that these plants sprout and grow and bloom and die with no one there to record them. Or they may not grow here at all anymore. When the West Fork of the Gila River shifts course, it alters tiny microclimates. That might, for example, kill off one of the rare orchids found in the area. The ongoing drought and rising temperatures may have affected others. A nearby wildfire certainly took out a few.

“The narrower a niche for a plant, the more likely it is to disappear,” Mutchnick says.

“Or not be detected,” Norris adds.

It’s also possible that the complex topography, including the cliffs facing the dwellings, which are steep enough to require rappelling to access their alcoves and niches, grow species they will never be able to reach, much less identify.

“Is that frustrating?” I ask Kleinman as we take in the view of that far side of the canyon.

“No,” he says, almost before I finish the question. “Every time we come here—and we’ve walked this canyon probably a hundred times among the three of us

—we find something. When there is so much still to discover right here, why would we worry about whether we can get over there?”

In addition to publishing a scientific paper on their findings, they hope to draft a guide to common plants for park visitors. A pamphlet or set of plaques could enliven the well-trod walk for visitors, coaching them to keep an eye out for the wildflowers growing alongside it.

These materials slow people down, or as Daniela Roth, botany program coordinator for the state’s Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Division, says, “alleviate plant blindness.”

Claret cup cactus (Echinocereus coccineus) and agrimony (Atrimonia striata) have been identified at Gila Cliff Dwellings.

Claret cup cactus (Echinocereus coccineus) and agrimony (Atrimonia striata) have been identified at Gila Cliff Dwellings.

Inventories like this one at the Gila are one of the only ways to see how much a place has changed, she says. A 2002–2003 inventory of plant and animal species commissioned by the National Park Service at the cliff dwellings noted the absence of three species of amphibians and three rodents that were reported as common at the park in the 1960s and ’70s.

“So it also teaches us to not dismiss things that are common today, because they might not be common tomorrow,” Roth says. “A rare species, they might wink out or can be easily overlooked, but to not find a common species anymore, that’s very disconcerting.”

Plant inventories are the only way to know that has happened. If all researchers have to go on is anecdotal reports that a species was once common and now it’s tough to find, there’s no way to confirm if that’s real decline or faulty recollections.

“If you don’t document it properly, it’s just a memory,” she says.

Russ Kleinman in his favorite workplace, the spectacular Gila National Forest.

Russ Kleinman in his favorite workplace, the spectacular Gila National Forest.

We walk far enough on the trail that runs along the West Fork of the Gila River to see the slots of other canyons that drain off the mesas, and the way the vegetation shifts a little, even just here, among horsetail ferns and golden currant blooming tiny yellow flowers with a pink flourish. Norris wades into the still backwater patches of the West Fork, pausing to look at the green depths. He seems to never stop examining the landscape, searching for the nuances others missed.

Weeks later, by phone, I learn the results. That tendril-like plant on a sunny shelf was the same species of Descurainia they’d already found. Here’s the other edge of the blade in a thorough survey: Memorizing 512 plants on a list is impossible. But in training their eyes to search for those species, they did find something new. The fern next to it, Pellaea wrightiana, or Wright’s cliffbrake fern, became species 513.

The perennial has been growing just off a congested section of trail where they usually keep on the path to avoid alarming other hikers who sometimes yell at them for hiking off-trail, as their research permit allows. It may have been there for years, Norris says, and “for whatever reason, our eyes weren’t pointing in the right direction.”

This summer, he planned to head back out, hoping to find one more species, one little plant that could nudge the count forward.

See more: View Russ Kleinman's photographs of more than 1,500 plant species in the Gila region.

Read more: Research on Gila botany has sprung offshoots: Richard Stephen Felger and Kelly Kindscher, along with James Thomas Verrier and Xavier Raj Herbst Khera, co-authored Field Guide to the Trees of the Gila Region of New Mexico, published this year by the University of New Mexico Press. After Felger and Kindscher presented some of the work during the Gila Natural History Symposium at Western New Mexico University, Felger led the effort to produce a book, which the rest of the team completed after his death in January.

Visit: Hike through Cliff Dweller Canyon and see the ancient Gila Cliff Dwellings via a one-mile loop trail with some steep sections. Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is open 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. year-round and located on NM 15. Park rangers staff tables to answer questions and share insights. Entrance is free.