(above) El Puerto del Sol (the Door to the Sun), by Armando Alvarez,

at El Cerro de Tomé, a pilgrimage site near Los Lunas.

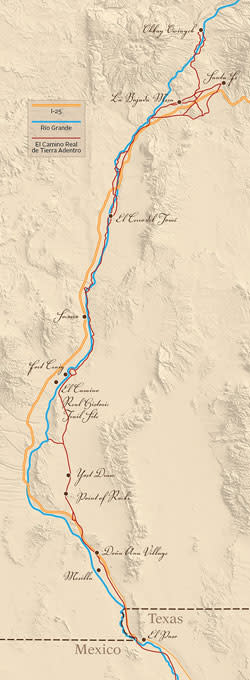

ARE YOU READY to rethink I-25? The state’s north-south artery is plenty picturesque as it wends its way through the state’s wide-open spaces, hilly swerves, and major cities, but there’s more to enjoy than meets the eye. I-25 follows a route trekked by prehistoric puebloans before Spanish conquistadors renamed it El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro and followed it to colonize New Mexico.

Sure, you could whiz up from the Mesilla Valley to Santa Fe in four hours. Instead, we suggest you drive into the past. Take a few detours, or even a few days, to discover El Camino Real: a multicentury Royal Road trip.

From the state’s 1598 founding as a Spanish colony to the 1878 arrival of the railroad, El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro wove the history and heritage of Spain and Mexico into a future America. This was formally recognized in 2000, when El Camino Real’s legacy of multicultural connection and exchange, and its role in the living history of New Mexico and the United States, led to its distinction as a National Historic Trail.

Today, traces of El Camino Real, which pre-dates both Jamestown and Plymouth Rock, remain imprinted across New Mexico in the form of wagon ruts, earthen swales, and gravestones. Historic towns, churches, buildings, archaeological sites, military forts, and natural landmarks hold memories of those who passed through. And many of the ancient communities in the riverside chain of Native pueblos on the route thrive to this day.

This month, history buffs gather in Santa Fe to celebrate New Mexico’s three National Historic Trails: El Camino Real, the Santa Fe Trail, and the Old Spanish Trail (see “Need to Know” and 3trailsconferencesantafe.org). Scholarly lectures and field trips offer participants a wagon train’s worth of trail trivia. For an in-depth experience of the oldest of these trails, the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management have recently made El Camino Real richly accessible every day of the year with directional signage, visitor centers, wayside exhibits, and interpretive information.

In 1849, Valentin Maese erected a two-room log-and-adobe home for his family just east of what would become the Mesilla plaza. Today, Maese’s house is the site of the plaza’s elegant, gilded Double Eagle Restaurant. A symbol of Mesilla’s evolution from a gritty frontier town to one of New Mexico’s grandest historical communities, it’s the perfect place to get your bearings and launch your journey into the equally gritty and grand history of El Camino Real.

Spanning some 400 miles across New Mexico and a portion of West Texas, El Camino Real comprises the northernmost segment of a 1,600-mile trail originating in Mexico City. Following Spain’s 1521 conquest of Mexico, the trail was developed to transport silver to Mexico City, the capital of New Spain. It was part of a vast Spanish network of caminos reales (royal roads) and maritime routes that connected and supplied Spain’s colonies in the Americas to Europe and beyond.

By the late 16th century, the trail stretched some 900 miles north to the mining district of Santa Barbara (in modern-day Chihuahua). There, in early 1598, Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate launched a daring journey into the rugged northern frontier, which had yet to be conquered by Spain. Oñate departed with 129 Spanish soldiers and their families, Franciscan friars, farmers, laborers, servants, and slaves. They traveled on horseback and on foot in a caravan of oxcarts and mule wagons, with thousands of head of livestock.

Crossing the Rio Grande at El Paso del Norte—today’s El Paso, Texas—Oñate continued north into modern-day New Mexico along an ancient route that had linked a chain of Native pueblos along the river corridor to Mexican tribes and trading centers since at least the 13th century. It ultimately led the expedition north of what is now Santa Fe to Ohkay Owingeh, which Oñate proclaimed as San Juan de los Caballeros, the first capital of New Mexico. (In 1610, the capital and El Camino Real’s terminus were moved south to Santa Fe.) Meanwhile, the Spanish usurped full control of the pueblo trail, largely restricting its use to the transport of Spanish goods and settlers.

Initially, Spanish caravans journeyed north every three to seven years, though, over time, the frequency increased to sustain the colony. Carrying as much as three tons of cargo, and averaging 10 miles a day, a one-way caravan trip took six months—if it was successful. Comanche, Apache, Navajo, and Ute warriors continually attacked caravans and raided Spanish and pueblo settlements alike. Lives were also lost in the Jornada del Muerto (Journey of the Dead Man), a waterless, 90-mile stretch of desert at the trail’s southern end.

Set between the Caballo and San Andres mountains, the Jornada was forged as a shortcut to a rugged river crossing. It saved days of travel, but the trade-off was that travelers and livestock had to survive three days in sweltering heat without a place to replenish water, food, or firewood. Those who died of exposure include German trader Bernardo Gruber, who in 1670 cut through the desert while escaping prison and a charge of witchcraft by the Spanish Inquisition. His remains were found at a site now known as La Cruz del Alemán (the Cross of the German), and his death inspired the Jornada’s name.

Just as rest areas dot I-25 today, parajes (rest stops or campsites) were established every 10 to 20 miles along El Camino Real for travelers’ respite and protection. Although occasional springs, seeps, and puddles formed in the Jornada del Muerto in times of good rain, the parajes of San Diego to the south and Fray Cristóbal to the north provided dependable rest and refreshment on either side of the journey.

For Spaniards far from home, the trail was the path to preserving cultural and religious traditions, communicating with loved ones, and maintaining a European cultural identity. For the pueblos, the trail symbolized religious persecution, servitude, taxation, and disease. By the late 17th century, pueblo leaders had had enough. On August 10, 1680, a majority of the pueblos attacked settlements throughout the colony. They burned down mission churches and killed 21 Franciscan priests before converging on Santa Fe, where Spanish survivors took shelter in the Casas Reales, the Plaza-based seat of the Spanish government. Now known as the Palace of the Governors (the sole survivor of the original Casas Reales), the building endures as the heart of the New Mexico History Museum.

Nine days later, the Spaniards surrendered the palace. They followed El Camino Real on foot 400 miles south to El Paso, where they remained until 1693, when Governor Don Diego de Vargas and other exiles traveled back up the trail and re-established control of Santa Fe. Other Spanish and Native refugees from New Mexico stayed in their newly founded communities of Socorro del Sur, Ysleta del Sur, and San Elizario. In what is now the El Paso area, descendants of these communities live among spectacular mission churches, a military presidio, and other historic buildings symbolizing the post-revolt occupation.

By the mid-18th century, Spanish-pueblo relations took on a more mutually tolerant tone. The pueblos adopted Spanish tools, livestock, agricultural resources, and new artistic and architectural techniques, and shared their local materials and know-how with the Spaniards. El Camino Real was important to the prosperity and cultural identity of both groups. Annual commercial caravans imported practical and luxury goods, and sent buckskins, piñon nuts, and other homegrown goods south for sale in Mexico.

In 1821, Mexico’s independence from Spain brought the end of regional trade restrictions. The resulting creation of the 800-mile Santa Fe Trail extended El Camino Real’s trade reach from Santa Fe to Missouri. It also ultimately gave US Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny a direct path to the Santa Fe Plaza, where the American flag was raised in 1846.

Realizing El Camino Real’s vital role in controlling the region, Army officials improved the trail and built a string of notable forts and garrisons along its route between Socorro and El Paso.

When the railroad arrived at Ratón Pass in 1878, El Camino Real’s importance took a hit. The trains carried in boxcars what mules and oxen had once hauled in wagons or on their backs, and their unparalleled ease and speed soon rendered the trail obsolete.

In time, through disuse, erosion, and development, the trail receded into the landscape. But its practicality as a transportation corridor could not be ignored. In 1905, New Mexico Highway 1, the territory’s first modern highway, was constructed roughly along the trail route. Eventually, I-25 cut a north-south swath along the trail’s path through the center of the state. In 2006, the New Mexico Rail Runner began following the Río Grande route through central New Mexico to the state capital. Spaceport America, another symbol of daring exploration, broke ground in 2009 on land bisected by El Camino Real. A tour bus takes visitors to the Spaceport grounds via Alemán Road.

Today’s El Camino Real is a living trail that invites you to find your own path through the state’s historic cultural landscapes. Although not all trail sections are open to the public, this south-north itinerary includes many extraordinary stops. (Southbound travelers can also follow the route in reverse.)

MESILLA PLAZA AND HISTORIC DISTRICT (DOÑA ANA COUNTY)

Today’s Mesilla, a small walking town, is a preservation model for communities along El Camino Real.

In 1848, driven by anti-American sentiment, 60 families from nearby Doña Ana moved south to an area on El Camino Real claimed by both Mexico and the United States. The 1854 Gadsden Purchase made Mesilla part of the New Mexico Territory. The transition turned Mesilla into a major military supply center and trade hub on El Camino Real.

With the army protecting the town from Apache Indian attacks, Mesilla rose in a ring of unique buildings that sheltered residents and businesses around a central plaza. By the close of the 1860s, it was the biggest city between San Diego and San Antonio, and one of the region’s rowdiest, most politically influential trade towns. In 1871, one of the New Mexico Territory’s bloodiest incidents took place during a political parade on the plaza. Drunken rival Democrats and Republicans rioted, leaving nine dead and 50 wounded.

Mesilla’s prominence faded 10 years later, when the railroad bypassed Mesilla for nearby Las Cruces. Returning to their agricultural roots, Mesilleros maintained their historic architecture, acequias, and farmlands.

A National Historic Landmark, today the plaza is home to many longtime residents, including J. Paul Taylor, an influential former state legislator whose family mindfully merged and expanded two historic adobe structures—a mercantile and a merchant’s residence—into a larger residence. Called the Taylor-Barela-Reynolds building, it houses a historic collection of New Mexican art and furnishings, and is designated to become a New Mexico Historic Site (see mynm.us/jpaultaylor).

For an authentic taste and feel of old Mesilla, duck into the corner El Patio Bar, pull up a stool by the door, and watch the plaza passersby. Or stroll beyond the plaza, where the town’s acequias and blocks of traditional residential buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. oldmesilla.org

GETTING THERE: The Mesilla Plaza and Historic District are located two miles southwest of Las Cruces. From the north, take I-25 to I-10 to Exit 140. From the south, take I-10 to Exit 140.

DOÑA ANA VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT (DOÑA ANA COUNTY)

Five miles north of Las Cruces, the original El Camino Real (now Cristo Rey Street) cuts directly through Doña Ana, the oldest permanent Hispano settlement in southern New Mexico. Established under the Mexican government in 1843, the town was built at the former ranch and El Camino Real paraje of Doña Ana María de Córdoba, whose history is mostly a mystery except for the village name. To thwart persistent Apache and Comanche attacks, residents designed the town as a cordillera, or linear village, of shoulder-to-shoulder homes with windowless facades and heavily fortified doors.

The only town on both sides of the Jornada del Muerto, Doña Ana was an essential stop for El Camino Real travelers and traders. By 1852, when it was named the political seat of the new Doña Ana County, the town boasted general stores and a saloon, dance hall, and courthouse. But complaints of overcrowding, and a growing military presence following the 1845 Mexican-American War, led some residents to head down El Camino Real to Mesilla. Others left to establish Las Cruces’ original town site, today’s Mesquite Historic District: an eclectic, non-gentrified community of 700 historic homes and buildings.

Doña Ana’s two-block core of 27 historic structures remains much as it was when it was built in 1843—a grid of rectangular blocks in a traditional Spanish-Mexican village plan. The town is quietly residential; tourists are welcome to walk or drive the trail. Be sure and stop by southern New Mexico’s oldest church, Our Lady of Candelaria, which melds Spanish, Mexican, and New Mexican architectural elements.

GETTING THERE: Doña Ana Village Historic District is located off I-25, just south of NM 320. From I-25, take Exit 9, turn west on NM 320, and proceed 4 miles. Turn left onto Dusty Lane, driving around the village church to Cristo Rey Street.

Thirty miles from I-25, a half-mile-loop trail delivers trekkers,

Thirty miles from I-25, a half-mile-loop trail delivers trekkers,

after a brief but intense climb, to this dramatic vista.

YOST DRAW AND POINT OF ROCKS (Sierra County)

For a taste of the challenges endured by those who dared this desert stretch of El Camino Real, hiking Yost Draw’s 3.8-mile trail section is a must. One of the most scenic, thrilling, and best-preserved pathways on El Camino Real, it highlights clearly defined pathways, deep arroyos, cobblestone ramps, and varying vegetation that reflect centuries of caravan traffic. The site’s bilingual interpretive signage provides a well-marked self-guided tour.

It’s a short climb east to the Yost Draw interpretive trail. Caution is advised; in the heat of day, the trek’s remoteness and ruggedness are exacerbated. When you reach the overlook where the interpretive tour begins, El Camino Real’s south-north path comes into view, marked by a dark strip of giant yucca and overgrown mesquite. As hikers step down the sandy escarpment, dense vegetation gives way to subtle swales and clear stretches of roadway, while musky smells of mesquite, tarbush, and creosote fill the air. The trail leads to the escarpment edge, a steep and rocky slope with stunning views of El Camino Real as it continues its course north through the Jornada del Muerto. You’ll also catch sight of Spaceport America.

Nearby, the towering basalt out-cropping known as Point of Rocks is one geographical landmark that helped travelers keep their bearings through the desert passage. Located about a day into the northbound desert journey, the base of the ridge offered a sheltered camping spot. For south-bound travelers, the ridge was a welcome reminder that water was 10 miles away. Today, you can access it from a county road; a climb up an interpretive half-mile loop trail offers sweeping views. The bluff overlooks a section of El Camino Real that runs between the escarpment and the eastern edge of the floodplain beyond.

GETTING THERE: The Yost Draw and Point of Rocks trailheads are located 20 miles and 30 miles, respectively, from I-25 on Sierra CR A013. From the south, take I-25 to Upham Exit 35 and Sierra CR E072, which turns into CR E070, which turns into CR A013 (Upham Road). From the north, take I-25 to Exit 79, then head east on NM 51 to Engle, and south on CR A013 (Upham Road).

This striking bit of architecture is surrounded by miles of rugged ranchland. Inside, you can observe dramatic exhibits about El Camino Real’s traversers and watch a short film about the camino’s history. Wagon ruts are visible from the observation deck.

This striking bit of architecture is surrounded by miles of rugged ranchland. Inside, you can observe dramatic exhibits about El Camino Real’s traversers and watch a short film about the camino’s history. Wagon ruts are visible from the observation deck.

FORT CRAIG AND EL CAMINO REAL HISTORIC TRAIL SITE (Socorro County)

The gentle flap of an American flag in an empty landscape inspires a visitor to imagine the ghostly Fort Craig as a fully occupied US Army garrison on the middle Río Grande route of El Camino Real. For a short period in early 1862, nearly 4,000 troops lived and worked at this sprawling stone-and-adobe complex. The fort was built in 1854 on the mesa lands of the Piro Indians, once the southernmost of the pueblo tribes.

African-American members of the Buffalo Soldiers were among the infantry and cavalry units stationed at Fort Craig. With the 1861 launch of the Civil War and the Confederate capture of Fort Fillmore, south of Las Cruces, Fort Craig’s strategic El Camino Real location weakened Confederate forces before their final defeat at Glorieta Pass. The fort was permanently abandoned by 1885.

Now owned and operated by the Bureau of Land Management, Fort Craig offers year-round opportunities for hiking, photography, picnicking, and self-guided tours.

Be sure to include the nearby El Camino Real Historic Trail Site in your plans. Set in an award-winning building boasting a stylized ship design, the state-owned site is set on the path of the very trail it interprets, offering exhibitions, artifacts, events, and a dramatic overlook. mynm.us/cr_historicsite

GETTING THERE: Fort Craig and El Camino Real Historic Trail Site are located 36 miles north of Truth or Consequences and 35 miles south of Socorro. From the south, take I-25 to Exit 115. Follow signs to the fort or historic site. From the north, take I-25 to the San Marcial exit, then go east over the interstate and south about 11 miles on NM 1.

EL CERRO DEL TOMÉ (Valencia County)

The black basalt slopes of El Cerro de Tomé (Tomé Hill) rise 400 feet above the Río Grande floodplain, 10 miles south of Isleta Pueblo (near Albuquerque). There, a cross-studded summit and masonry shrine crown petroglyph-filled hillsides, remnants of the site’s history as a spiritual landmark on El Camino Real.

From prehistoric times to today, the hill has been a sacred site for local Native and Hispano peoples. Isleta residents marked the hill as the Pueblo’s southern boundary, conducting ceremonies there until the early 20th century.

In 1659, Tomé Domínguez de Mendoza received a royal land grant and built a home near the hill. He fled during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, but the area assigned by the 1739 Tomé Land Grant retained his name.

In the early 20th century, the faithful began summiting the hill on Good Friday. Today, the hill hosts a vibrant Good Friday pilgrimage and is a year-round destination for recreation and meditation. A small park at the base of the hill features La Puerta del Sol, a monumental sculpture by Armando Alvarez honoring the history of El Camino Real.

GETTING THERE: El Cerro de Tomé is about 25 miles south of Albuquerque and five miles south-east of Los Lunas, about a half-mile east of the junction of NM 47 and Tomé Hill Road. From the south: On I-25, take Exit 190 (south Belén). Continue on S. Main about 2 miles. Turn right on Reinken Ave. (NM 309) and go 2.4 miles. Turn left onto NM 47 and proceed 7.5 miles. Turn right onto Tomé Hill Road and go 1.2 miles to Tome Hill Park. From the north: Take I-25 through Albuquerque to Exit 223. Turn left on NM 47 and follow south through Isleta Pueblo, Bosque Farms, Peralta, and Valencia. Just after Valencia, turn left at NM 263. Follow to Sand Hill Road and turn right. Follow until you see the Cerro on your left and a parking area and small park on your right.

LA BAJADA MESA (Santa Fe County)

Moving through the Middle Río Grande Valley into northern New Mexico, a visit to Kuaua Ruins in Bernalillo, a prehistoric Tiwa Indian village dating to AD 1300, is a worthwhile detour. Though situated west of the route of El Camino Real, the site shows what one of the region’s largest Native pueblo settlements was like prior to the Spanish incursion (see mynm.us/coronadosite). The pueblo covered six acres with 1,200 dwellings and storage rooms, six underground ceremonial kivas, and three rectangular plazas.

With the Spaniards’ arrival, New Mexico was broken into two economic and governmental districts: the Río Abajo (lower river) and the Río Arriba (upper river). The dividing line was an ancient volcanic escarpment known as La Bajada (the Descent). Today, La Bajada Mesa intersects with I-25 about 10 miles southwest of Santa Fe, with Cochiti Pueblo lands beginning about halfway up the escarpment’s gentle six-mile slope. Stretching 600 feet high, the basalt mesa top was the most difficult route along El Camino Real for entering or departing Santa Fe. Before the 1860s, when the military improved the passage, only pedestrians and livestock could scale the mesa. Later, wagons and automobiles braved a harrowing switchback road with 23 hairpin turns. Even now, La Bajada’s rise into the capital tests the mettle of some low-cylinder cars.

The mesa is one of the most historically significant sections of El Camino Real, with remains of prehistoric stone piles from early agricultural grids, post-European tools and resources, and parallel roadways marking where caravans and livestock traveled side by side. The old road across the mesa, some of which is laid on top of El Camino Real, is rutted and fully exposed to wind, sun, and other tests of weather. A high-clearance SUV and adequate provisions for hiking or emergencies are advised, and rattlesnakes can be a risk.

While the landscape can be surveyed by car, a close-up view of the various El Camino Real tracks begs exploration on foot. The dramatic southerly view from the mesa top, overlooking the picturesque village of La Bajada, a former rest stop for El Camino Real travelers, rewards the intrepid.

GETTING THERE: La Bajada Mesa is located 18 miles from downtown Santa Fe. From the south and north: Exit onto Veterans Memorial Highway (NM 599) from I-25; continue to Airport Road and turn left. Take Airport Road about 3.1 miles until it turns into CR 56. Continue 3.3 miles to CR 56C and take a hard right turn, heading upslope to the west. Stay on CR 56C, which loops to the left and turns into Forest Road 24. Proceed on Santa Fe National Forest Road 24 for about seven miles to the escarpment edge. The mesa also crosses private and Bureau of Land Management lands. Driving down the escarpment onto Cochiti Pueblo lands is prohibited without Pueblo permission.

SANTA FE PLAZA, PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS, FORT MARCY RUINS (Santa Fe County)

For many El Camino Real travelers and traders, the prize of surviving the trail was reaching the Spanish capital of Santa Fe. After the daunting La Bajada climb, many first stopped at the village of La Cíenega, where the paraje of El Rancho de las Golondrinas (the Ranch of the Swallows) offered overnight lodging and provisions. Today, the ranch is a living history museum (golondrinas.org) depicting Hispano life in 18th-and 19th-century New Mexico, including the history and heritage of El Camino Real. The museum’s annual fall harvest festival (October 1 and 2) is a perfect time to experience the daily life and color of those who settled along the trail.

The New Mexican capital and northern terminus of El Camino Real, the city developed as a center of government and international exchange. Constructed in 1610 on the Plaza’s north side, the adobe Palace of the Governors is one of the oldest, best-preserved buildings central to El Camino Real history. The Palace has been home to Spanish, Mexican, American, and pueblo Indian leaders, enduring various incarnations in structure and style, including its transformation into a multistory walled-in home of pueblo peoples who moved in after the Pueblo Revolt. Now boasting a long, shady portal where Native artisans sell handmade jewelry and more, the Palace is a National Historic Landmark. It overlooks the Plaza’s flagstone walkways, warm-weather grasses, shady park benches, and lively, year-round events.

While the Palace evolved as a visual icon of Santa Fe, the old Fort Marcy provided the best view of Santa Fe’s historic core. Within six days of the US Army’s 1846 occupation of the city, the fort’s construction got underway on an 80-foot bluff directly northeast of downtown. When finished, every angle of the irregular, star-shaped, earthen compound held all of Santa Fe within view, and within gunshot. Today, the ruins of Fort Marcy, located inside the 6.5-acre Prince Park, are a barely distinguishable arrangement of earthen mounds that trace the outline of the fort’s original foundations. A series of new interpretive wayside exhibits guides visitors through the site.

In addition to the ruins, Prince Park is a popular place for a picnic or a twilight view of the sunset over the city. A few steps down a short walkway from Fort Marcy, the tall, white Cross of the Martyrs, a prominent landmark visible from downtown, recognizes the memory of the 21 Franciscan priests and friars killed in the Pueblo Revolt. You can also reach it by ascending the handsome, switchbacking brick walkway (favored by lunch-hour exercisers) off Paseo de Peralta near Otero Street.

GETTING THERE: The Santa Fe Plaza and Palace of the Governors are located in the historic heart of Santa Fe. Heading north along I-25, take either the St. Francis or Old Pecos Trail exit and follow the signs to downtown. Following US 285 south into Santa Fe, continue directly onto North Guadalupe Street to the San Francisco Street light and turn left. Follow San Francisco Street east to the Plaza. Fort Marcy Ruins is located in downtown Santa Fe, northeast of the Plaza and Palace of the Governors. From the Plaza, take Washington Avenue north to Artist Road and turn right. Follow Artist Road to Sunset Street and turn right. Turn left on Kearny Avenue and right on Prince Avenue, which leads directly to the parking lot of Prince Park.

Carmella Padilla

NEED TO KNOW

El Camino Real is the subject of a new online travel itinerary offering in-depth trail history and photography and detailed visitation information. The guide was developed by the National Register of Historic Places and the National Trails Intermountain Region of the National Park Service, which, with the Bureau of Land Management, is charged with increasing trail awareness and accessibility. Trail areas are generally accessible on foot or bicycle, and, when appropriate, by car or on horseback. Admission is charged at some sites, and not all are wheelchair-accessible. Hikers should exercise caution, especially in hot weather and in particularly remote areas. Santa Fe’s Three Trails Conference is September 17–20. For more details, visit 3trailsconferencesantafe.org