Above: A petroglyph panel in the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument.

AS WE WALKED THE SHORT DISTANCE to our destination in the Sierra de las Uvas, northwest of Las Cruces, I noticed our honored guest gently rubbing the sides of his face. Only later did I learn that anointing oneself with pollen is a common spiritual ritual of indigenous people. This unassuming act was a different type of discovery for me, a reminder that there is almost always something new to learn when I visit these places.

As our intended site came into view, our guest paused in silence and then broke into song. While the words were foreign to me, they actually may have been the least foreign element of our outing. The melody danced on the desert breeze, and the uplifting spirit of the moment lingered long after our group of elected officials, invited guests, and local advocates for outdoor conservation departed.

We had gathered on this day, nearly a decade ago, in a part of what was to become the Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument in 2014. Our honored guest, a member of the Kiowa nation, was on a pilgrimage to trace the migratory journeys of his people through ancestral sites across the country. This site featured a number of petroglyphs left by those who called the area home long before European people arrived.

I’m blessed to have grown up in southern New Mexico, where an evening spent roasting hot dogs skewered on sharpened yucca stalks over a sandy arroyo campfire served as prime entertainment—and cuisine—on many a boyhood summer evening. We explored the desert in every way imaginable to a child and jumped at any opportunity for an excursion to the nearby foothills and mountains.

As the years and decades rolled by, I have enjoyed countless outings into our Chihuahuan Desert to hike and camp, search for wildlife, and enjoy the serenity of our nearby public lands. When I learned President Barack Obama was considering declaring a large portion of the mountains in Doña Ana County a national monument, I was curious what could be documented as “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest,” as required by the Antiquities Act of 1906. And thus began my own journey and a newfound appreciation for the special character and diversity of cultural sites that reside in our own backyard. Especially its ancient rock art.

Above: A sun star greets these petroglyph neighbors.

Above: A sun star greets these petroglyph neighbors.

INDIGENOUS ROCK ART appears all across New Mexico and around the world.

For novices hoping to experience its beauty, three exceptional places are Petroglyph National Monument, in Albuquerque; the Three Rivers Petroglyph Site, north of Alamogordo; and La Cieneguilla Petroglyphs, west of Santa Fe. After you get familiar with what to expect, some common themes emerge in terms of where rock art occurs. But for me, nothing rivals the sense of discovery that comes with finding a site on your own.

Take serious note: These are sensitive cultural sites. Still regarded as spiritual places by nearby tribes, they can easily be desecrated by visitors who fail to recognize them as national treasures. When a rock art image is defaced, it can never be undone. Even the oils from your palm can be detrimental, especially for pictographs, which are painted rather than pecked. As a result, the locations of many such archaeological sites are intentionally kept obscure.

In general, rock art exists where early inhabitants lived. People chose their living sites based on the availability of food, water, shelter, and perhaps defensibility. If you focus on those elements and find habitation sites, there is a fair chance that rock art is nearby.

Another fundamental requirement for rock art is a good surface, akin to an artist’s canvas. Smooth rock with a sheen or “desert varnish” that reveals a different color when chipped or pecked away is common, especially in volcanic regions. Caves offered both shelter and good surfaces for art, but they are relatively rare here. I know of roughly 50 rock art sites within the Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument, and at least twice that many across south-central New Mexico. A few sites are vast, like Three Rivers, with thousands of images, but most consist of a few panels, or perhaps even a single image. Large or small, each site is unquestionably unique, with a character and backdrop all its own.

Interpreting the meaning of rock art can be a field of study unto itself. The images often include geometric forms, handprints, animals, and various human forms. I both admire and respect that rock art bears an important cultural and spiritual significance for the indigenous people of this region—the images may speak to elements of their religious practices and origin stories or perhaps simply highlight nearby landmarks. These days, even archaeologists hesitate to ascribe meanings to each image. I don’t wish to intrude by prying into whatever private meanings they may hold for the descendants of those who created them.

I prefer to view the images as a gift—an indelible artistic record that spurs my imagination about the life and times of the artist. To that end, the local Tigua Indians of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, the oldest permanent settlement in this area, use the name Speaking Rock as a symbol of their tribe. I like to think of rock art as a bridge over the vast canyons and arroyos of time, a bridge that connects the creator of each image with those who view the art, speaking to each of us individually—much as we appreciate other art forms in our own personal ways.

As our forefathers pondered how to manage the vast frontier of the American West, one of their greatest foresights was the decision to place large tracts of land and water in the public trust, making us all stewards of those places. That’s how I found myself on a hike with a Kiowa elder and other dignitaries. Together, we not only built grassroots support that led to federal recognition for and protection of the Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks area but we also enjoyed countless hours documenting the hidden jewels within its vast and varied terrain, which has seen everything from ancient peoples to Billy the Kid to Apollo astronaut training sessions.

Beyond rock art, the Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument is filled with adventures. Like an earthbound constellation, its four sections serve as an outdoor lover’s cardinal directions surrounding Las Cruces. Within them, you’ll find everything from volcanic landscapes to rocky peaks, narrow canyons, wildflowers, ponderosa pines, and the popular Dripping Springs Natural Area. Only by exploring them will you discover their hidden gems. But I warn you: If the rock art exploration bug afflicts you, the effects can be lasting. I celebrate that affliction, and trust that it will remain with me for many years to come.

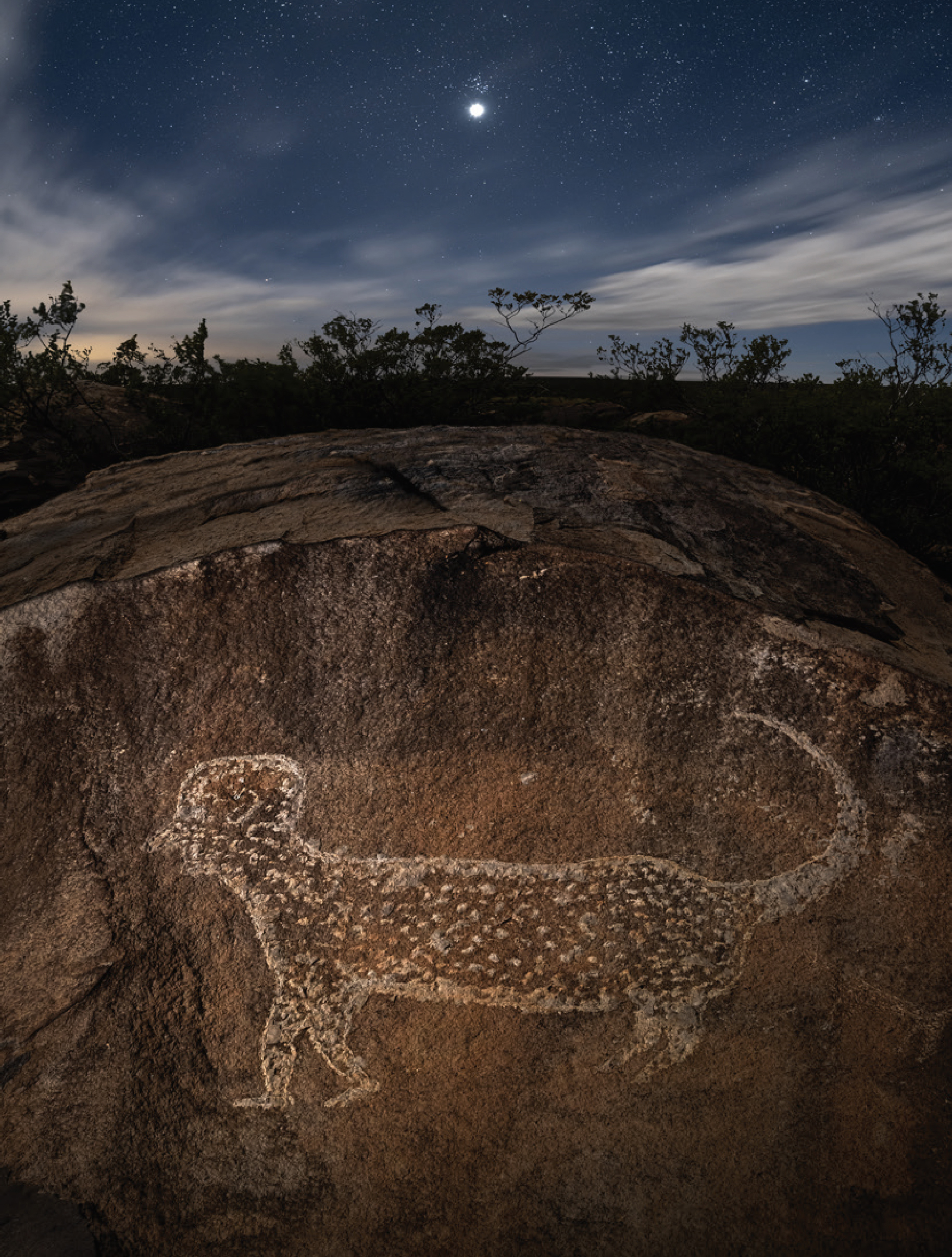

Above: Venus overlooks an iconic petroglyph.

Above: Venus overlooks an iconic petroglyph.

Hitting the Peaks

The Bureau of Land Management oversees the Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument (blm.gov/visit/omdp). For a comprehensive guide to its trails, pick up the 2018 guidebook Exploring Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument, by Devon Fletcher with David Soules. During the summer, plan on morning adventures; afternoon temps can hit 100 degrees. Take plenty of water, let people know where you’re going, and keep an eye out for rattlesnakes and other hazards. If you find examples of rock art, feel free to take photographs, but do not touch or vandalize them. Admire them as you would any culturally significant item.