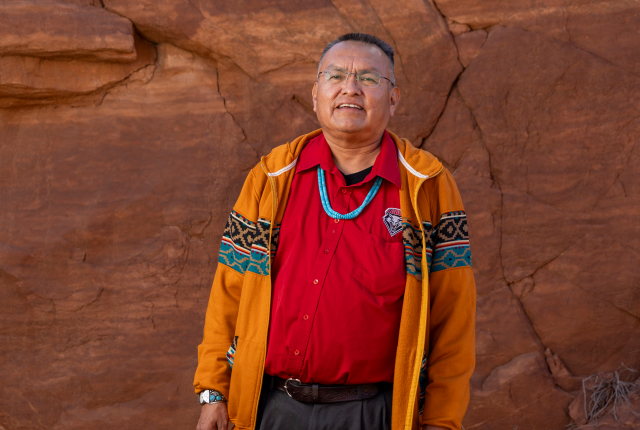

DR. SHAWN SECATERO IS ONLY 54, but his students already consider him a treasured elder. A member of Cañoncito Band of Navajos (Diné) and associate professor of education at the University of New Mexico, Secatero founded the groundbreaking Promoting our Leadership, Learning, and Empowering our Nations (POLLEN) program in 2016 to train Native American educators to be principals.

“Higher education has historically been predominantly a White space,” says April Yazza, a second-year Diné doctoral student in the current cohort. “It’s a totally foreign space to be in.”

Educational inspiration was hard to come by where Secatero grew up, on the remote To’hajiilee reservation, about 30 miles west of Albuquerque. Raised in a two-room house, he attended Bureau of Indian Affairs schools, where he was taught the basics but was never encouraged to go to college. “We were never taught our culture, our language—just told to graduate and try to get a job,” Secatero says. “For those of us who wanted to excel, our opportunities were limited.”

Secatero took inspiration from his elders and listened to his parents, who valued education and prayed for his success. He became the first in his high school to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree.

At the heart of Secatero’s work is his Corn POLLEN teaching model, which is based on 16 pillars of health and leadership. It harks back to ancient Indigenous cultures that used corn pollen to recognize outstanding leadership attributes.

“It’s holistic, it’s diverse,” explains Secatero. “It involves spiritual, mental, physical, and social well-being.”

The model grew from his dissertation, which examined the components of persistence and success gleaned from interviews with 23 graduate-level Native American lawyers, doctors, and teachers. “At some point in the process, I got stuck, and the elders said, ‘Make a corn POLLEN model,’ ” he says. “That’s how I finished it in 2009.”

Secatero never considered locating his program anywhere but UNM. “When you are given the opportunity to work at the flagship university of your state, you gotta go all out,” he says. POLLEN has since trained 50 educators working with Native American students in schools across the United States and throughout the world.

Drawn by word of the program’s success, students now come to UNM to enroll in his POLLEN program from all across the globe, then return to their communities to teach and lead. “We want educators who are culturally responsive as well as homegrown,” says Secatero. “They know their community, their language, and the culture.”

It’s important to produce Native leaders, Yazza says, because Native students—and their teachers—succeed when they can see themselves reflected in the educational process. “He encouraged me to call up from my Diné traditions and taught me how to empower myself,” says Yazza.

Secatero also works with high school students to earn dual college credits and runs the Striking Eagle Leadership Academy, a 90-minute educational workshop that’s part of a winter basketball tournament at UNM. “Basketball brings our Native community together and promotes physical well-being,” he says. “Some students have never been on a college campus before.”

This month, Secatero’s POLLEN organization expects to graduate 10 more leaders committed to educating Native American students. “My students at the high school are my children, and my cohort is like my family,” he says. “The students in my dual-credit classes bring purpose and joy to my life.”